“It was the best of times; it was the worst of times.” This opening line of Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities is germane to the state of Jewish-Arab relations this year. This has been a period in which, on the international level, Israel and a number of Arab nations established formal relations, and on the internal level, Israel’s Arab minority seemed to be heading towards full integration within society. Israeli Arabs garnered respect and appreciation for their prominent role in combating COVID and by their outpouring of empathy and tangible support in response to the tragedy at Meron. Suddenly, now, this has all been overshadowed by extensive rioting and attacks against Jews, the burning of homes and synagogues, and the firing of thousands of missiles from Gaza. This turnabout has left many bewildered, searching for a way to integrate these contradictory realities and asking what this tells us about the future.

“It was the best of times; it was the worst of times.” This opening line of Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities is germane to the state of Jewish-Arab relations this year. This has been a period in which, on the international level, Israel and a number of Arab nations established formal relations, and on the internal level, Israel’s Arab minority seemed to be heading towards full integration within society. Israeli Arabs garnered respect and appreciation for their prominent role in combating COVID and by their outpouring of empathy and tangible support in response to the tragedy at Meron. Suddenly, now, this has all been overshadowed by extensive rioting and attacks against Jews, the burning of homes and synagogues, and the firing of thousands of missiles from Gaza. This turnabout has left many bewildered, searching for a way to integrate these contradictory realities and asking what this tells us about the future.Many factors underlie this complexity. That said, in both of these processes, the positive and the negative, religious identity plays a major role. The name of the peace agreements with the Gulf states, “The Abraham Accords,” highlights the common ancestor of both faiths. Within Israel, increased Arab involvement in politics and the call for tolerance and partnership between Jews and Arabs has emerged specifically from the Arab party that spotlights religion: Mansour Abbas’s Islamic Movement, known as Ra’am. On the other hand, the igniting of violence against Jews also has a religious context – the month of Ramadan and the fact that the violence is a response to claims of threats to Al Aqsa.

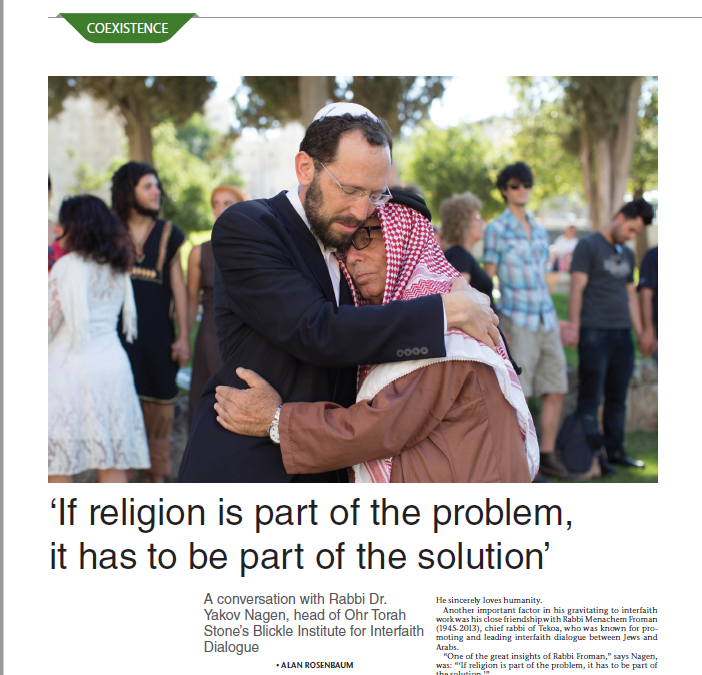

In regard to the tensions and conflicts in Israel and the Middle East, Rabbi Menachem Froman used to say “If religion is part of the problem, then it will have to be part of the solution.” Gaining a deeper understanding of Jewish-Muslim relations, can help guide these relations and influence both the micro and the macro processes.

But for me, the issue of relations between Judaism and Islam goes beyond a social or political question. It gets to the heart of who I am as a Jew, how I can serve God most fully, and what my role is in realizing visions of redemption. I believe that the Jewish people should not be passive in awaiting the fulfillment of the biblical vision of the future, but instead takes an active part in bringing them to fruition, including that of calling to God globally: to “call upon the name of the Lord, to worship Him of one accord” (Zephaniah 3:9). Just as we have devoted ourselves to fulfilling visions of redemption such as the return to Zion and rebuilding the land, we must devote no less energy to promoting the universal vision that can come about only through partnership with other peoples in serving God.

Here, relations with Islam play a significant role. Both faiths believe in the same God. Maimonides maintained that “concerning the unity of God, [Muslims] are not at all in error.” Islam recognizes this commonality as well; Sura 29 of the Quran states unequivocally regarding the Jews that “our God and their God is one.” Jews and Muslims believe in and serve the same God.

Modern rabbis continue to apply this principle. Rabbi Avigdor Nebenzahl, the former chief rabbi of Jerusalem’s Old City, once condemned the desecration of a mosque not on grounds of tolerance, but simply because God is worshipped in a mosque, and it is therefore forbidden to vandalize it. He explained the God that Muslims pray to in their houses of worship is the same God that Jews address in our synagogues. This voice was echoed this week in Mansour Abbas’s visit to a synagogue in Lod and his condemnation of its desecration as a violation of Islam’s respect for sacred sites. Similarly, Rabbi Shmuel Salant, the Chief Rabbi of Jerusalem for many decades of the nineteenth century, was careful not to walk in front of a Muslim at prayer, saying that the Divine Presence graced the spot.

Muslim sources that grant a special status to the Jewish people and to the revelation at Mount Sinai. For example, the Quran mentions Moses 135 times, while Muhammad is mentioned a scant four times. Jews and Muslims recognize one another as cousins, descendants of Abraham through Isaac and Ishmael. As we read in the book of Genesis, families can spark the strongest hatreds and the most horrific conflicts – but they also share the deepest, most meaningful ties.

Two opposing Islamic views on Jews

Still, the reality is more complex. Historically, Islam has presented two contrasting faces to Jews. The harsh face includes Muhammad’s massacre of the Jewish Qurayza tribe (based on the claim that when he fought the people of Mecca these Jews planned to betray him and support his enemies). Fueled in part by medieval Muslim-Jewish polemics, many Muslim religious leaders and scholars claim that the Jewish Bible is a distortion of the original book given to the Jews by God and that furthermore the Bible has been abrogated by the Quran.

Yet Islam also has a benevolent face relating to Jews and Judaism The Quran grants to Jews (and Christians) the honorific title of “Ahl al-Kitab,” People of the Book, and also stress the importance of the Torah and esteem the Jews as the chosen people. In more modern times, the Muslim kings of Morocco would send emissaries to synagogues in times of drought, to ask them to pray for rain.

We must understand the roots of this complex relationship if we want to promote its positive aspects and strive toward healing and fellowship. When we recognize both the agreeable and the negative elements of our history and interaction – and the reasons for them – it will guide us to reinforce the positive and mend the problems from their roots. The goal is not to justify or whitewash the wounds of the past but to find the path to repair our relationship – for our sake, for their sake, and for the sake of fulfilling God’s designs for the world. What, then, are the roots of this complex relationship?

To answer this question, we must distinguish between Islam’s approach to Judaism and its approach to Jews. Islamic sources express great respect for Judaism and its texts, but often hostility toward Jews. The Quran consistently articulates respect for the Torah and even for the Jewish people, who bear the obligation to observe the Torah’s commandments and who will be rewarded for proper observance in the next world. This is true not only of early sources, from the Mecca period, but also of the later ones, from the al-Medina period, as well. Take, for example, the following verses from the al-Medina period:

We revealed the Torah, wherein there is guidance and light. Thereby did prophets, who had submitted themselves, judge the Jews, and so did the rabbis and judges. They judged by the book of Allah, for they had been entrusted to keep it and bear witness to it. (Sura 5:44)

For each of you we have appointed a Law and a way of life. And had Allah so willed, He would have made you one single community; instead, [He gave each of you a Law and a way of life] in order to test you by what He gave you. Vie, then, one with another in good works, as to Allah you will all return and He will then make you understand the truth concerning the matters upon which you disagreed. (Sura 5:48)

The Quran affirms the truth of the holy books of earlier religions. It states that each one contains the laws and practices one must follow, and that the Torah specifically, revealed from heaven, provides “guidance and light.” A Hadith relates that when some Jews asked Muhammad to render a halachic decision, he instructed them to bring a Torah scroll and a Jew who knew how to read it. When the Torah scroll arrived, Muhammad rose from his cushion to accommodate it and honor it (Sunan Abu Dawud 40).

The Quran’s tempered criticism of Jews

It is also true, however, that the Quran contains sharp criticism of the Jews. Some stemmed from Muhammad’s observation that there were Jews who did not keep the Torah they were committed to keep. For example, the infamous statement that “the Jews are monkeys” was said about Jews whose commitment to Shabbat observance was tried by God and found wanting. The Quran also adopted criticism of Jews from reproaches of the Israelites in the Torah, such as after the sin of the Golden Calf.

But Muhammad had not always been hostile to Jews. When he was still in Mecca, he voiced respect for Jews themselves, as well as for their religion. It was only later, in al-Medina, that Muhammad turned against them. He had seen himself as the natural extension of Judaism, and was bitterly disappointed that the Jews rejected his message and his movement and remained steadfast in their tradition. This, combined with other historical factors, led to a volatile situation and to his adopting a harsh, even violent, approach to the Jews. It accounts for the contrast between the severe criticism of Jews and the legitimacy he accorded Judaism.

It also enables us to understand why the Quran’s rejection of the Jews is not categorical. Professor Tamer Metwally of Al-Madinah University in Saudi Arabia contrasts between early Christian theology, which saw the Jewish people as rejected by God, collectively responsible for the death of Jesus, and whose suffering as proof that they were accursed and sinful. The Quran, on the other hand, repeatedly tempers its criticism of Jews with the admonition that “they are not all alike,” and does not fundamentally reject Jews (e.g., Sura 3:113–15).

Could Islam ever develop a more positive approach to Judaism? To shed light on this question we can look to developments within Christianity, which was once far more hostile to Jews and Judaism than was Islam. The relationship between Christians and Jews was characterized by sharp theological polemics and bloodshed. But gradually, over many years, the Christian attitude has shifted – considerably.

While theological convictions of two thousand years cannot change overnight, a turning point was achieved in “Nostra aetate” in 1965. This declaration, commonly known as Vatican II, marked a dramatic turnaround in Christian-Jewish relations. The Commission of the Holy See for Religious Relations with the Jews issued an additional document, “The Gifts and Calling of God Are Irrevocable,” in 2015; it officially repudiated evangelizing Jews, based on a new recognition that God’s covenant with the Jewish people is still in force.

These changes are the products of copious effort over many years and of extensive discussion among key Jewish and Christian leaders. The process remains incomplete, and it will likely take years to fully heal and to foster perfect peace between the two religions and their adherents. Nevertheless, these developments in the Christian world attest to the possibility of great change if we are determined and persistent, even if we begin from the most painful starting point.

The path to reconciliation

We would be naïve to imagine that the path to reconciliation and mutual appreciation between Jews and Muslims will be simple or quick. We need to contend with the severe traumas from the past, the violence and hatred in the present, and the widespread mutual antipathy between the populations.

At base, however, the hostility does not arise from the core of either religion. In fact, our foundational stories, rather than contradicting one another, strengthen each other: The Jewish view of Abraham as “the father of nations” underlies our ability to be a blessing to other nations, to fulfill our purpose, and to reveal God’s design for the world. There are billions of people who worship God, who recognize Abraham as their patriarch, and who respect the Jewish path to serving God. This glorifies God’s name and expands the Abrahamic influence.

For Muslims, Judaism is vital for their own religious story. Professor Metwally, in his book Bias against Judaism in Contemporary Writings: Recognition and Apology, asserts that since Islam is built upon a progression of different emissaries and revelations, striking at Judaism strikes at one of the building blocks of Islam and thereby undermines its faith. Jews and Judaism provide essential testimony to certain pillars of Islamic doctrine: the revelation at Sinai and the chain of divine prophecy. The Quran itself calls upon adherents to turn to the Jews to corroborate faith (Sura 10:94).

We can build on the existing framework within Islam of respect and appreciation for Jews. As Jews, we actually have a role to play in intra-Muslim conversations, since Islam recognizes the importance of the Jewish link in the chain of revelation and opens dialogue with Jews. Understanding the roots of the alienation and violence facilitates our ability to heal the rift, restore mutual respect, and liberate ourselves from antagonism.

I firmly believe that through personal encounters and interfaith dialogue on the basis of these principles we can create change. Let us have no illusions that this process will be quick; the conditions are too complex for easy answers. But we must proceed, knowing that “the eternal nation does not fear the long journey.”